Mīrzā Muhammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrukh ( Ulugh Beg)

1394-1449

Born: 1394 in Soltaniyeh, Timurid, Persia (now Iran)

Died: 27 October 1449 in Samarkand, Timurid empire

Mīrzā Muhammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrukh (Chagatay: میرزا محمد طارق بن شاہ رخ, Persian: میرزا محمد تراغای بن شاہ رخ) better known asUlugh Beg (الغ بیگ) (March 22, 1394 in Sultaniyeh, Persia – October 27, 1449, Samarkand) was a Timurid ruler as well as anastronomer, mathematician and sultan. His commonly known name is not truly a personal name, but rather a moniker, which can be loosely translated as "Great Ruler" or "Patriarch Ruler" and was the Turkic equivalent of Timur's Perso-Arabic title Amīr-e Kabīr.[1]His real name was Mīrzā Mohammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrokh. Ulugh Beg was also notable for his work in astronomy-related mathematics, such as trigonometry and spherical geometry. He built the great Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand between 1424 and 1429. It was considered by scholars to have been one of the finest observatories in the Islamic world at the time and the largest in Central Asia.[2] He built the Ulugh Beg Madrasah (1417–1420) in Samarkand and Bukhara, transforming the cities into cultural centers of learning in Central Asia.[3] He was also a mathematics genius of the 15th century — albeit his mental aptitude was perseverance rather than any unusual endowment of intellect.[4] His Observatory is situated in Samarkand which is in Uzbekistan. He ruled Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, southern Kazakhstan and most of Afghanistan for almost half a century from 1411 to 1449.Early life[edit]

He was a grandson of the great conqueror, Timur (Tamerlane) (1336–1405), and the oldest son of Shah Rukh, both of whom came from the Turkicized[6] Barlas tribe of Transoxiana (now Uzbekistan). His mother was a noblewoman named Goharshad, daughter of the representative Turkic[7][8] of tribal aristocracy Giyasitdin Tarhan. Ulugh Beg was born in Sultaniyeh in Persia during Timur's invasion. As a child he wandered through a substantial part of the Middle East and India as his grandfather expanded his conquests in those areas. After Timur's death, however, and the accession of Ulugh Beg's father to much of the Timurid Empire, he settled in Samarkand, which had been Timur's capital. After Shah Rukh moved the capital to Herat (in modern Afghanistan), sixteen-year-old Ulugh Beg became his governor in Samarkand in 1409. In 1411, he became the sovereign ruler of the whole Mavarannahr khanate.

Science[edit]

The teenaged ruler set out to turn the city into an intellectual center for the empire. Between 1417 and 1420, he built a madrasa("university" or "institute") on Registan Square in Samarkand (currently in Uzbekistan), and he invited numerous Islamic astronomers andmathematicians to study there. The madrasa building still survives. Ulugh Beg's most famous pupil in astronomy was Ali Qushchi (died in 1474). He was also famous in the fields of medicine and poetry. He used to debate with other poets about contemporary social issues. He liked to debate in a poetic style, called "Bahribayt" among local poets. According to the medical book "Mashkovskiy" which is in Russian language, Ulugh Beg discovered the mixture of alcohol with garlic, apparently preserving it to help treat conditions like diarrhea, headache, stomachache, intestine illnesses. He also offered advice for newly married couples: Indicating recipes contains nuts, dried apricot, dried grape etc. that he claimed to be useful to increase men`s virility. This recipe has been given in Ibn Sina`s books also.

Astronomy[edit]

His own particular interests concentrated on astronomy, and, in 1428, he built an enormous observatory, called the Gurkhani Zij, similar to Tycho Brahe's later Uraniborg as well as Taqi al-Din's observatory in Istanbul. Lacking telescopes to work with, he increased his accuracy by increasing the length of his sextant; the so-called Fakhri sextant had a radius of about 36 meters (118 feet) and the optical separability of 180" (seconds of arc).

Using it, he compiled the 1437 Zij-i-Sultani of 994 stars, generally considered[who?] the greatest star catalogue between those ofPtolemy and Brahe, a work that stands alongside Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's Book of Fixed Stars. The serious errors which he found in previous Arabian star catalogues (many of which had simply updated Ptolemy's work, adding the effect of precession to the longitudes) induced him to redetermine the positions of 992 fixed stars, to which he added 27 stars from Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's catalogue Book of Fixed Stars from the year 964, which were too far south for observation from Samarkand. This catalogue, one of the most original of the Middle Ages, was first edited by Thomas Hyde at Oxford in 1665 under the title Tabulae longitudinis et latitudinis stellarum fixarum ex observatione Ulugbeighi and reprinted in 1767 by G. Sharpe. More recent editions are those byFrancis Baily in 1843 in vol. xiii of the Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society and by Edward Ball Knobel in Ulugh Beg's Catalogue of Stars, Revised from all Persian Manuscripts Existing in Great Britain, with a Vocabulary of Persian and Arabic Words (1917).

In 1437, Ulugh Beg determined the length of the sidereal year as 365.2570370...d = 365d 6h 10m 8s (an error of +58 seconds). In his measurements within many years he used a 50 m high gnomon. This value was improved by 28 seconds in 1525 by Nicolaus Copernicus, who appealed to the estimation of Thabit ibn Qurra (826–901), which had an error of +2 seconds. However, Beg later measured another more precise value as 365d 5h 49m 15s, which has an error of +25 seconds, making it more accurate than Copernicus' estimate which had an error of +30 seconds. Beg also determined the Earth's axial tilt as 23.52 degrees, which remained the most accurate measurement for hundreds of years. It was more accurate than later measurements by Copernicus and Tycho Brahe.[9]

Mathematics[edit]

In mathematics, Ulugh Beg wrote accurate trigonometric tables of sine and tangent values correct to at least eight decimal places.

Death[edit]

Ulugh Beg's scientific expertise was not matched by his skills in governance. When he heard of the death of his father Shahrukh Mirza, Ulugh Beg went to Balkh, where he heard that his nephew Ala-ud-Daulah Mirza bin Baysonqor, son of Ulugh's brother Baysonqor, had claimed the emirship of the Timurid Empire in Herat. Consequently Ulugh Beg marched against Ala-ud-Daulah and met him in battle atMurghab. Having won this battle, Ulugh Beg advanced toward Herat and massacred its people in 1448, but Ala-ud-Daulah's brother Mirza Abul-Qasim Babur bin Baysonqorcame to his aid, defeating Ulugh Beg. Ulugh Beg retreated to Balkh, where he found that its governor, his oldest son Abdal-Latif Mirza, had rebelled against him. Another civil war ensued. Within two years, he was beheaded by the order of his own eldest son while on his way to Mecca.[10] Eventually, his reputation was rehabilitated by his nephew,Abdallah Mirza (1450–1451), who placed Ulugh Beg's remains in the mausoleum of Timur in Samarkand, where they were found by archeologists in 1941.

Mīrzā Muhammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrukh (Chagatay: میرزا محمد طارق بن شاہ رخ, Persian: میرزا محمد تراغای بن شاہ رخ) better known as Ulugh Beg (الغ بیگ) (March 22, 1394 in Sultaniyeh, Persia – October 27, 1449, Samarkand) was a Timurid ruler as well as an astronomer, mathematician and sultan. His commonly known name is not truly a personal name, but rather a moniker, which can be loosely translated as "Great Ruler" or "Patriarch Ruler" and was the Turkic equivalent of Timur's Perso-Arabic title Amīr-e Kabīr.[1] His real name was Mīrzā Mohammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrokh. Ulugh Beg was also notable for his work in astronomy-related mathematics, such as trigonometry and spherical geometry. He built the great Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand between 1424 and 1429. It was considered by scholars to have been one of the finest observatories in the Islamic world at the time and the largest in Central Asia.[2] He built the Ulugh Beg Madrasah (1417–1420) in Samarkand and Bukhara, transforming the cities into cultural centers of learning in Central Asia.[3] He was also a mathematics genius of the 15th century — albeit his mental aptitude was perseverance rather than any unusual endowment of intellect.[4] His Observatory is situated in Samarkand which is in Uzbekistan. He ruled Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, southern Kazakhstan and most of Afghanistan for almost half a century from 1411 to 1449.

Contents [hide]

1 Early life

2 Science

2.1 Astronomy

2.2 Mathematics

3 Death

4 Legacy

5 Exhumation

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

Early life[edit]

Jade dragon cup that once belonged to Ulugh Beg, 1420-1449

AD, British Museum.[5]

He was a grandson of the great conqueror, Timur (Tamerlane)

(1336–1405), and the oldest son of Shah Rukh, both of whom came from the

Turkicized[6] Barlas tribe of Transoxiana (now Uzbekistan). His mother was a

noblewoman named Goharshad, daughter representative Turkic[7][8] tribal

aristocracy Giyasitdin Tarhan. Ulugh Beg was born in Sultaniyeh in Persia

during Timur's invasion. As a child he wandered through a substantial part of

the Middle East and India as his grandfather expanded his conquests in those

areas. After Timur's death, however, and the accession of Ulugh Beg's father to

much of the Timurid Empire, he settled in Samarkand, which had been Timur's

capital. After Shah Rukh moved the capital to Herat (in modern Afghanistan),

sixteen-year-old Ulugh Beg became his governor in Samarkand in 1409. In 1411,

he became the sovereign ruler of the whole Mavarannahr khanate.

Science

The teenaged ruler set out to turn the city into an

intellectual center for the empire. Between 1417 and 1420, he built a madrasa

("university" or "institute") on Registan Square in

Samarkand (currently in Uzbekistan), and he invited numerous Islamic

astronomers and mathematicians to study there. The madrasa building still

survives. Ulugh Beg's most famous pupil in astronomy was Ali Qushchi (died in

1474). He was also famous in the fields of medicine and poetry. He used to

debate with other poets, socials regarding the contemporary issues. He liked to

debate in a poetic style, called "Bahribayt" among local poets.

According to the medical book "Mashkovskiy" which is in Russian

language, Ulugh Beg discovered the mixture of alcohol with garlic, apparently

preserving it to help treat conditions like diarrhea, headache, stomachache,

intestine illnesses. He also offered advice for newly married couples:

Indicating recipes contains nuts, dried apricot, dried grape etc. that he

claimed to be useful to increase men`s virility. This recipe has been given in

Ibn Sina`s books also.

Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand. In Ulugh Beg's time,

these walls were lined with polished marble.

Astronomy

His own particular interests concentrated on astronomy, and,

in 1428, he built an enormous observatory, called the Gurkhani Zij, similar to

Tycho Brahe's later Uraniborg as well as Taqi al-Din's observatory in Istanbul.

Lacking telescopes to work with, he increased his accuracy by increasing the

length of his sextant; the so-called Fakhri sextant had a radius of about 36

meters (118 feet) and the optical separability of 180" (seconds of arc).

Using it, he compiled the 1437 Zij-i-Sultani of 994 stars,

generally considered[who?] the greatest star catalogue between those of Ptolemy

and Brahe, a work that stands alongside Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's Book of Fixed

Stars. The serious errors which he found in previous Arabian star catalogues

(many of which had simply updated Ptolemy's work, adding the effect of

precession to the longitudes) induced him to redetermine the positions of 992

fixed stars, to which he added 27 stars from Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's catalogue

Book of Fixed Stars from the year 964, which were too far south for observation

from Samarkand. This catalogue, one of the most original of the Middle Ages,

was first edited by Thomas Hyde at Oxford in 1665 under the title Tabulae

longitudinis et latitudinis stellarum fixarum ex observatione Ulugbeighi and

reprinted in 1767 by G. Sharpe. More recent editions are those by Francis Baily

in 1843 in vol. xiii of the Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society and by

Edward Ball Knobel in Ulugh Beg's Catalogue of Stars, Revised from all Persian

Manuscripts Existing in Great Britain, with a Vocabulary of Persian and Arabic

Words (1917).

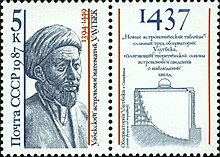

Ulugh Beg and his astronomical observatory scheme, depicted

on the 1987 USSR stamp. He was one of Islam's greatest astronomers during the

Middle Ages. The stamp says "Uzbek astronomer and mathematician Ulugbek"

in Russian.

In 1437, Ulugh Beg determined the length of the sidereal

year as 365.2570370...d = 365d 6h 10m 8s (an error of +58 seconds). In his

measurements within many years he used a 50 m high gnomon. This value was

improved by 28 seconds in 1525 by Nicolaus Copernicus, who appealed to the

estimation of Thabit ibn Qurra (826–901), which had an error of

+2 seconds. However, Beg later measured another more precise value as 365d

5h 49m 15s, which has an error of +25 seconds, making it more accurate than

Copernicus' estimate which had an error of +30 seconds. Beg also

determined the Earth's axial tilt as 23.52 degrees, which remained the most

accurate measurement for hundreds of years. It was more accurate than later

measurements by Copernicus and Tycho Brahe.[9]

Mathematics[edit]

In mathematics, Ulugh Beg wrote accurate trigonometric

tables of sine and tangent values correct to at least eight decimal places.

Death[edit]

Ulugh Beg's scientific expertise was not matched by his

skills in governance. When he heard of the death of his father Shahrukh Mirza,

Ulugh Beg went to Balkh, where he heard that his nephew Ala-ud-Daulah Mirza bin

Baysonqor, son of Ulugh's brother Baysonqor, had claimed the emirship of the

Timurid Empire in Herat. Consequently Ulugh Beg marched against Ala-ud-Daulah

and met him in battle at Murghab. Having won this battle, Ulugh Beg advanced

toward Herat and massacred its people in 1448, but Ala-ud-Daulah's brother

Mirza Abul-Qasim Babur bin Baysonqor came to his aid, defeating Ulugh Beg.

Ulugh Beg retreated to Balkh, where he found that its governor, his oldest son

Abdal-Latif Mirza, had rebelled against him. Another civil war ensued. Within

two years, he was beheaded by the order of his own eldest son while on his way

to Mecca.[10] Eventually, his reputation was rehabilitated by his nephew,

Abdallah Mirza (1450–1451), who placed Ulugh Beg's remains in the mausoleum of

Timur in Samarkand, where they were found by archeologists in 1941.

Ulugh Beg was the grandson of the conqueror Timur, who is

often known as Tamerlane (from Timur-I-Leng meaning Timur the Lame, a title of

contempt used by his Persian enemies). Although in this archive we are

primarily interested in Ulugh Beg's achievements in mathematics and astronomy,

we need to examine the history of the area since it had such a major impact on

Ulugh Beg's life.

Timur, Ulugh Beg's grandfather, came from the Turkic Barlas

tribe which was a Mongol tribe that was living in Transoxania, today

essentially Uzbekistan. He united several Turko-Mongol tribes under his

leadership and set out on a conquest, with his armies of mounted archers, of

the area now occupied by Iran, Iraq, and eastern Turkey.

Shortly after his grandson Ulugh Beg was born, Timur invaded

India and by 1399 he had taken control of Delhi. Timur continued his conquests

by extending his empire to the west from 1399 to 1402, winning victories over

the Egyptian Mamluks in Syria and the Ottomans in a battle near Ankara. Timur

died in 1405 leading his armies into China.

After Timur's death his empire was disputed among his sons.

Ulugh Beg's father Shah Rukh was the fourth son of Timur and, by 1407, he had

gained overall control of most of the empire, including Iran and Turkistan

regaining control of Samarkand. Samarkand had been the capital of Timur's

empire but, although his grandson Ulugh Beg had been brought up at Timur's

court, he was seldom in that city. When Timur was not on one of his military

campaigns he moved with his army from place to place and his court, including

his grandson Ulugh Beg, travelled with him.

In 1409 Shah Rukh decided to make Herat in Khorasan (today

in western Afghanistan) his new capital. Shah Rukh ruled there making it a

trading and cultural centre. He founded a library there and became a patron of

the arts. However Shah Rukh did not give up Samarkand, rather he decided to

give it to his son Ulugh Beg who was more interested in making the city a

cultural centre than he was in politics or military conquest. Although Ulugh

Beg was only sixteen years old when his father put him in control of Samarkand,

he became his father's deputy and he became ruler of the Mawaraunnahr region.

Ulugh Beg was primarily a scientist, in particular a

mathematician and an astronomer. However, he certainly did not neglect the

arts, writing poetry and history and studying the Qur'an. In 1417, to push

forward the study of astronomy, Ulugh Beg began building a madrasah which is a

centre for higher education. The madrasah, fronting the Rigestan Square in

Samarkand, was completed in 1420 and Ulugh Beg then began to appoint the best

scientists he could find to positions there as lecturers.

Ulugh Beg invited al-Kashi to join his madrasah in

Samarkand, as well as around sixty other scientists including Qadi Zada. There

is little doubt that, other than Ulugh Beg himself, al-Kashi was the leading

astronomer and mathematician at Samarkand. Letters which al-Kashi wrote to his

father have survived. These were written from Samarkand and give a wonderful

description of the scientific life there. The contents of one of these letters

has only recently been published, see [5].

In the letters al-Kashi praises the mathematical abilities

of Ulugh Beg but of the other scientists in Samarkand, only Qadi Zada earned

his respect. Ulugh Beg led scientific meetings where problems in astronomy were

freely discussed. Usually these problems were too difficult for all except

al-Kashi and the letters confirm that al-Kashi was the closest collaborator of

Ulugh Beg at his madrasah in Samarkand.

In addition to the madrasah, Ulugh Beg built an observatory

at Samarkand, the construction of this beginning in 1428. The Observatory,

which was circular in shape, had three levels. It was over 50 metres in

diameter and 35 metres high. The director of the Observatory was Ali-Kudschi, a

Muslim astronomer. Al-Kashi and other mathematicians and astronomers appointed

to the madrasah also worked at Ulugh Beg's Observatory.

Among the instruments specially constructed for the

Observatory was a quadrant so large that part of the ground had to be removed

to allow it to fit in the Observatory. There was also a marble sextant, a

triquetram and an armillary sphere. The achievements of the scientists at the

Observatory, working there under Ulugh Beg's direction and in collaboration

with him, are discussed in detail in [4]. This excellent book records the main

achievements which include the following: methods for giving accurate

approximate solutions of cubic equations; work with the binomial theorem; Ulugh

Beg's accurate tables of sines and tangents correct to eight decimal places;

formulae of spherical trigonometry; and of particular importance, Ulugh Beg's

Catalogue of the stars, the first comprehensive stellar catalogue since that of

Ptolemy.

This star catalogue, the Zij-i Sultani, set the standard for

such works up to the seventeenth century. Published in 1437, it gives the

positions of 992 stars. The catalogue was the results of a combined effort by a

number of people working at the Observatory including Ulugh Beg, al-Kashi, and

Qadi Zada. As well as tables of observations made at the Observatory, the work

contained calendar calculations and results in trigonometry.

The trogonometric results include tables of sines and

tangents given at 1° intervals. These tables display a high degree of accuracy,

being correct to at least 8 decimal places. The calculation is built on an

accurate determination of sin 1° which Ulugh Beg solved by showing it to be the

solution of a cubic equation which he then solved by numerical methods. He

obtained

sin 1° = 0.017452406437283571

The correct approximation is

sin 1° = 0.017452406437283512820

which shows the remarkable accuracy which Ulugh Beg

achieved.

Observations made at the Observatory brought to light a

number of errors in the computations of Ptolemy which had been accepted without

question up to that time. Data from his Observatory allowed Ulugh Beg to

calculate the length of the year as 365 days 5 hours 49 minutes 15 seconds, a

fairly accurate value. He produced data relating to the Sun, the Moon and the

planets. His data for the movements of the planets over a year is, like so much

of his work, very accurate [1]:-

... the difference between Ulugh Beg's data and that of

modern times relationg to [Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus] falls within the

limits of two to five seconds.

Ulugh Beg's politics were not up to his science and, after

his father's death in 1447, he was unable to retain power despite being an only

son. He was eventually put to death at Samarkand at the instigation of his own

son 'Abd al-Latif. His tomb was discovered in 1941 in the mausoleum built by

Timur in Samarkand. It was discovered that Ulugh Beg had been buired in his

clothes which is known to indicate that he was considered a martyr. The

injuries inflicted on him were evident when his body was examined [1]:-

... the third cervical vertebra was severed by a sharp

instrument in such a way that the main portion of the body and an arc of that

vertebra were cut cleanly; the blow, struck from the left, also cut through the

right corner of the lower jaw and its lower edge.

List of Iranian scientists

[hide] v t e

Medicine in the medieval Islamic world

Physicians

7th century

Al-Harith ibn Kalada and his son Abu Hafsa Yazid Bukhtishu

Masarjawaih Ibn Abi Ramtha al-Tamimi Rufaida Al-Aslamia Ibn Uthal

8th century

Bukhtishu family Ja'far al-Sadiq

9th century

Albubather Bukhtishu family Jabril ibn Bukhtishu Jābir ibn

Hayyān Hunayn ibn Ishaq and his son Yahya ibn Sarafyun Al-Kindi Masawaiyh

Shapur ibn Sahl Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari Al-Ruhawi Yuhanna ibn Bukhtishu

Salmawaih ibn Bunan

10th century

Qusta ibn Luqa Abu ul-Ala Shirazi Abul Hasan al-Tabari

Al-Natili Qumri Abu Zayd al-Balkhi Isaac Israeli ben Solomon 'Ali ibn al-'Abbas

al-Majusi Abu Sahl 'Isa ibn Yahya al-Masihi Muvaffak Muhammad ibn Zakariya

al-Razi Ibn Juljul Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi Ibn al-Jazzar Al-Kaŝkarī Ibn Abi

al-Ashʿath Ibn al-Batriq Ibrahim ibn Baks

11th century

Abu 'Ubayd al-Juzjani Alhazen Ali ibn Ridwan Avicenna

Ephraim ibn al-Za'faran Ibn al-Wafid Abdollah ibn Bukhtishu Ibn Butlan Ibn

al-Kattani Ibn Jazla Masawaih al-Mardini Ali ibn Yusuf al-Ilaqi Ibn Al-Thahabi

Ibn Abi Sadiq Ali ibn Isa al-Kahhal

12th century

Abu al-Bayan ibn al-Mudawwar Ahmad ibn Farrokh Ibn Hubal

Zayn al-Din Gorgani Maimonides Serapion the Younger Ibn Zuhr Ya'qub ibn Ishaq

al-Israili Abu Jafar ibn Harun al-Turjali Averroes Ibn Tufail Al-Ghafiqi Ibn

Abi al-Hakam Abu'l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī Al-Samawal al-Maghribi Ibn al-Tilmīdh

Ibn Jumay‘

13th century

Sa'ad al-Dawla Al-Shahrazuri Rashidun al-Suri Amin al-Din

Rashid al-Din Vatvat Abraham ben Moses ben Maimon Da'ud Abu al-Fadl Al-Dakhwar

Ibn Abi Usaibia Joseph ben Judah of Ceuta Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi (medieval

writer) Ibn al-Nafis Zakariya al-Qazwini Najib ad-Din-e-Samarqandi Qutb al-Din

al-Shirazi Ibn al-Quff

14th century

Muhammad ibn Mahmud Amuli Al-Nagawri Aqsara'i Zayn-e-Attar

Mansur ibn Ilyas Jaghmini Mas‘ud ibn Muhammad Sijzi Najm al-Din Mahmud ibn

Ilyas al-Shirazi Nakhshabi Sadid al-Din al-Kazaruni Yusuf ibn Ismail al-Kutubi

Ibn al-Khatib Rashid-al-Din Hamadani

15th century

Abu Sa'id al-Afif Muhammad Ali Astarabadi Husayni

Isfahani Burhan-ud-din Kermani Şerafeddin Sabuncuoğlu Muhammad ibn Yusuf

al-Harawi Nurbakhshi Shaykh Muhammad ibn Thaleb

16th century

Hakim-e-Gilani Abul Qasim ibn Mohammed al-Ghassani Taqi

ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf Dawud al-Antaki

Concepts

Psychology Ophthalmology

Works

The Canon of Medicine Anatomy Charts of the Arabs The

Book of Healing Book of the Ten Treatises of the Eye De Gradibus Al-Tasrif

Zakhireye Khwarazmshahi Adab al-Tabib

Centers

Bimaristan Nur al-Din Bimaristan Al-'Adudi

Influences

Ancient Greek medicine

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar