Ibn Battuta

(1304 -

1369C.E.)

| Ibn Battuta | |

|---|---|

| Native name | أبو عبد الله محمد بن عبد الله اللواتي الطنجي بن بطوطة |

| Born | February 25, 1304 Tangier, Morocco |

| Died | 1369 (aged 64–65) Morocco |

| Occupation | Islamic scholar, Jurist, Judge,explorer, geographer |

| Era | Medieval era |

| Religion | Islam |

Ibn Baṭūṭah (/ˌɪbənbætˈtuːtɑː/ Arabic: أبو عبد الله محمد بن عبد الله اللواتي الطنجي بن بطوطة, ʾAbū ʿAbd al-Lāh Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Lāh l-Lawātī ṭ-Ṭanǧī ibn Baṭūṭah), or simply Ibn Battuta (ابن بطوطة) (February 25, 1304 – 1368 or 1369), was a Moroccan explorer ofBerber descent.[1] He is known for his extensive travels, accounts of which were published in the Rihla (lit. "Journey"). Over a period of thirty years, Ibn Battuta visited most of the known Islamic world as well as many non-Muslim lands. His journeys included trips toNorth Africa, the Horn of Africa, West Africa and Eastern Europe, and to the Middle East, South Asia, Central Asia, Southeast Asiaand China. Ibn Battuta is generally considered one of the greatest travellers of all time.[2]

Early life and first hajj

All that is known about Ibn Battuta's life comes from the autobiographical information included in the account of his travels, which records that he was born into a family of Islamic legal scholars in Tangier, Morocco, on February 25, 1304, during the reign of the Marinid dynasty.[3] He claimed descent from a Berber tribe known as the Lawata.[4] As a young man he would have studied at a Sunni Malikimadh'hab, (Islamic jurisprudence) school, the dominant form of education in North Africa at that time.[5] In June 1325, at the age of twenty-one, Ibn Battuta set off from his hometown on a hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca, a journey that would take sixteen months. He would not see Morocco again for twenty-four years.[6]

He travelled to Mecca overland, following the North African coast across the sultanates of Abd al-Wadid and Hafsid. The route took him through Tlemcen, Béjaïa, and then Tunis, where he stayed for two months.[8] For safety, Ibn Battuta usually joined a caravan to reduce the risk of an attack by wandering Arab Bedouin. He took a bride in the town of Sfax, the first in a series of marriages that would feature in his travels.[9]

In the early spring of 1326, after a journey of over 3,500 km (2,200 mi), Ibn Battuta arrived at the port of Alexandria, which was at the time part of the Bahri Mamluk empire. He met two ascetic pious men in Alexandria. One was Sheikh Burhanuddin who is supposed to have foretold the destiny of Ibn Batuta as a world traveler saying "It seems to me that you are fond of foreign travel. You will visit my brother Fariduddin in India, Rukonuddin in Sind and Burhanuddin in China. Convey my greetings to them". Another pious man Sheikh Murshidi interpreted the meaning of a dream of Ibn Batutah that he was meant to be a world traveller.[10][11] He spent several weeks visiting sites in the area, and then headed inland toCairo, the capital of the Mamluk Sultanate and an important large city. After spending about a month in Cairo,[12] he embarked on the first of many detours within the relative safety of Mamluk territory. Of the three usual routes to Mecca, Ibn Battuta chose the least-travelled, which involved a journey up the Nile valley, then east to the Red Sea port of Aydhab,[a] Upon approaching the town, however, a local rebellion forced him to turn back.[14]

Ibn Battuta returned to Cairo and took a second side trip, this time to Mamluk-controlled Damascus. During his first trip he had encountered a holy man who prophesied that he would only reach Mecca by travelling through Syria.[15] The diversion held an added advantage; because of the holy places that lay along the way, including Hebron, Jerusalem, and Bethlehem, the Mamluk authorities spared no efforts in keeping the route safe for pilgrims. Without this help many travellers would be robbed and murdered.[16][b]

After spending the Muslim month of Ramadan in Damascus, he joined a caravan travelling the 1,300 km (810 mi) south to Medina, tomb of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. After four days in the town, he journeyed on to Mecca, where completing his pilgrimage he took the honorific status of El-Hajji. Rather than returning home, Ibn Battuta instead decided to continue on, choosing as his next destination the Ilkhanate, a MongolKhanate, to the northeast.[21]

Iraq and Persia[edit]

On 17 November 1326, following a month spent in Mecca, Ibn Battuta joined a large caravan of pilgrims returning to Iraq across the Arabian Peninsula.[22] The group headed north to Medina and then, travelling at night, turned northeast across the Najd plateau to Najaf, on a journey that lasted about two weeks. In Najaf, he visited the mausoleum of Ali, the Fourth Caliph.[23]

Then, instead of continuing on to Baghdad with the caravan, Ibn Battuta started a six-month detour that took him into Persia. From Najaf, he journeyed to Wasit, then followed the river Tigris south to Basra. His next destination was the town of Esfahān across the Zagros Mountains in Persia. He then headed south to Shiraz, a large, flourishing city spared the destruction wrought by Mongol invaders on many more northerly towns. Finally, he returned across the mountains to Baghdad, arriving there in June 1327.[24] Parts of the city were still ruined from the damage inflicted by Hulago Khan's invading army in 1258.[25]

In Baghdad, he found Abu Sa'id, the last Mongol ruler of the unified Ilkhanate, leaving the city and heading north with a large retinue.[26] Ibn Battuta joined the royal caravan for a while, then turned north on the Silk Road to Tabriz, the first major city in the region to open its gates to the Mongols and by then an important trading centre as most of its nearby rivals had been razed by the Mongol invaders.[27]

Ibn Battuta left again for Baghdad, probably in July, but first took an excursion northwards along the river Tigris. He visited Mosul, where he was the guest of the Ilkhanate governor,[28] and then the towns of Cizre (Jazirat ibn 'Umar) and Mardin in modern-day Turkey. At a hermitage on a mountain near Sinjar, he met a Kurdish mystic who gave him some silver coins.[c][31] Once back in Mosul, he joined a "feeder" caravan of pilgrims heading south to Baghdad, where they would meet up with the main caravan that crossed the Arabian Desert to Mecca. Ill with diarrhoea, he arrived in the city weak and exhausted for his second hajj.[32]

Arabian Peninsula[edit]

Ibn Battuta remained in Mecca for some time (the Rihla suggests about three years, from September 1327 until autumn 1330). Problems with chronology, however, lead commentators to suggest that he may have left after the 1328 hajj.[d]

After the hajj in either 1328 or 1330, he made his way to the port of Jeddah on the Red Sea coast. From there he followed the coast in a series of boats making slow progress against the prevailing south-easterly winds. Once in Yemen he visited Zabīd and later the highland town of Ta'izz, where he met the Rasulid dynasty king (Malik) Mujahid Nur al-Din Ali. Ibn Battuta also mentions visiting Sana'a, but whether he actually did so is doubtful.[33] In all likelihood, he went directly from Ta'izz to the important trading port of Aden, arriving around the beginning of 1329 or 1331.[34]

Somalia[edit]

From Aden, Ibn Battuta embarked on a ship heading for Zeila on the coast of Somalia. He then moved on to Cape Guardafui further down the Somalia seaboard, spending about a week in each location. Later he would visit Mogadishu, the then pre-eminent city of the "Land of the Berbers" (بلد البربر Balad al-Barbar, the medieval Arabic term for the Horn of Africa).[35][36][37]

When Ibn Battuta arrived in 1331, Mogadishu stood at the zenith of its prosperity. He described it as "an exceedingly large city" with many rich merchants, noted for its high-quality fabric that was exported to other countries, including Egypt.[38] Ibn Battuta added that the city was ruled by a Somali Sultan, Abu Bakr ibn Sayx 'Umar,[39][40] who was originally from Berbera in northern Somalia and spoke bothSomali (referred to by Battuta as Mogadishan, the Benadir dialect of Somali) and Arabic with equal fluency.[40][41] The Sultan also had a retinue of wazirs (ministers), legal experts, commanders, royal eunuchs, and assorted hangers-on at his beck and call.[40]

Swahili Coast[edit]

Ibn Battuta continued by ship south to the Swahili Coast, a region then known in Arabic as the Bilad al-Zanj ("Land of the Zanj"),[42] with an overnight stop at the island town of Mombasa.[43] Although relatively small at the time, Mombasa would become important in the following century.[44] After a journey along the coast, Ibn Battuta next arrived in the island town of Kilwa in present-day Tanzania,[45] which had become an important transit centre of the gold trade.[46] He described the city as "one of the finest and most beautifully built towns; all the buildings are of wood, and the houses are roofed with dīs reeds."[47]

Ibn Battuta recorded his visit to the Kilwa Sultanate in 1330, and commented favorably on the humility and religion of its ruler, Sultan al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman, a descendant of the legendary Ali ibn al-Hassan Shirazi. He further wrote that the authority of the Sultan extended from Malindi in the north to Inhambane in the south and was particularly impressed by the planning of the city, believing it to be the reason for Kilwa's success along the coast. From this period date the construction of the Palace of Husuni Kubwa and a significant extension to the Great Mosque of Kilwa, which was made of Coral stones and the largest Mosque of its kind. With a change in the monsoon winds, Ibn Battuta sailed back to Arabia, first to Oman and the Strait of Hormuz then on to Mecca for the hajj of 1330 (or 1332).

Anatolia[edit]

After his third pilgrimage to Mecca, Ibn Battuta decided to seek employment with the Muslim Sultan of Delhi, Muhammad bin Tughluq. In the autumn of 1330 (or 1332) he set off for the Seljuq controlled territory of Anatolia with the intention of taking an overland route to India.[48] He crossed the Red Seaand the Eastern Desert to reach the Nile valley and then headed north to Cairo. From there he crossed the Sinai Peninsula to Palestine and then travelled north again through some of the towns that he had visited in 1326. From the Syrian port of Latakia, a Genoese ship took him (and his companions) toAlanya on the southern coast of modern-day Turkey.[49] He then journeyed westwards along the coast to the port of Antalya.[50] In the town he met members of one of the semi-religious fityan associations.[51] These were a feature of most Anatonian towns in the 13th and 14th centuries. The members were young artisans and had at their head a leader with the title of Akhis.[52] The associations specialised in welcoming travellers. Ibn Battuta was very impressed with the hospitality that he received and would later stay in their hospices in more than 25 towns in Anatolia.[53] From Antalya Ibn Battuta headed inland to Eğirdirwhich was the capital of the Hamid dynasty. He spent Ramadan (June 1331 or May 1333) in the city.[54]

From this point the itinerary across Anatolia in the Rihla is confused. Ibn Battuta describes travelling westwards from Eğirdir to Milas and then skipping 420 km (260 mi) eastward past Eğirdir to Konya. He then continues travelling in an easterly direction, reaching Erzurum from where he skips 1,160 km (720 mi) back to Birgi which lies north of Milas.[55] Historians believe that Ibn Battuta visited a number of towns in central Anatolia, but not in the order that he describes.[56][e]

Central Asia and Southern Asia[edit]

From Sinope he took a sea route to the Crimean Peninsula, arriving in the Golden Horde realm. He went to the port town of Azov, where he met with the emir of the Khan, then to the large and rich city of Majar. He left Majar to meet with Uzbeg Khan's travelling court (Orda), which was in the time near Beshtau mountain. From there he made a journey to Bolghar, which became the northernmost point he reached, and noted its unusually (for a subtropics dweller) short nights in summer. Then he returned to Khan's court and with it moved to Astrakhan. Ibn Battutah noted that as soon as he arrived in Bulghar in the month of Ramadan the call for evening prayer (maghrib salah) was announced from a mosque. He attended the prayer. After a short while he attended Isha prayer and Tarawih prayer (special Ramadan prayer). After this prayer he was to about take some rest. In the meantime his companion made him hurry to eat suhur (late night meal for fasting in Ramadan)as the dawn was about to begin. No sooner he finished the suhur the Muazzin made the call for dawn (fajr) prayer. He did not get even a short time for sleep. Ibn Battutah also informed that while in Bulghar he wanted to travel further north into the land of darkness. The land is all through snow covered (northern Siberia) and the only means of transport is dog drawn sled. There lived a mysterious people who were reluctant to show their appearance. But they traded with southern people in a peculiar way. Southern merchants bring various goods and place them in an open area on the snow in the night and returned to their tents. Next morning they come to the place again and found their merchandise were taken by the mysterious people and in exchange they put various skins of fur animals which are used for making valuable coats, jackets, and other winter garments. The trade is done between merchants and mysterious people without seeing each other. As Ibn Battutah was not a merchant and seeing no benefit of going there he abandoned the travel to this land of darkness.[59]

When they reached Astrakhan, Öz Beg Khan had just given permission for one of his pregnant wives, Princess Bayalun, a daughter of Greek Emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos, to return to her home city of Constantinople to give birth. Ibn Battuta talked his way into this expedition, which would be his first beyond the boundaries of the Islamic world.[60]

Arriving in Constantinople towards the end of 1332 (or 1334), he met the Greek emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos. He visited the great church ofHagia Sophia and spoke with a Christian Orthodox priest about his travels in the city of Jerusalem. After a month in the city, Ibn Battuta returned to Astrakhan, then arrived in the capital city Sarai al-Jadid and reported his travelling account to Sultan Öz Beg Khan (r. 1313–1341). Thereafter he continued past the Caspian and Aral Seas to Bukhara and Samarkand. There he visited the court of another Mongolian king, Tarmashirin (r. 1331–1334) of the Chagatai Khanate.[61] From there, he journeyed south to Afghanistan, ruled by the Mongols, then crossed into India via the mountain passes of the Hindu Kush. In the Rihla, he mentions these mountains and the history of the range in slave trading.[62][63] He wrote,

Ibn Battuta and his party reached the Indus River on 12 September 1333.[64] From there, he made his way to Delhi and became acquainted with the sultan, Muhammad bin Tughluq.

South Asia[edit]

Muhammad bin Tughluq was renowned as the wealthiest man in the Muslim world at that time. He patronized various scholars, Sufis, qadis,viziers and other functionaries in order to consolidate his rule. As with Mamluk Egypt, the Tughlaq Dynasty was a rare vestigial example of Muslim rule in Asia after the Mongol invasion. On the strength of his years of study in Mecca, Ibn Battuta was appointed a qadi, or judge, by the sultan.[65] However, he found it difficult to enforce Islamic law beyond the sultan's court in Delhi, due to lack of Islamic appeal in India.[66]

From the Rajput Kingdom of Sarsatti, Battuta visited Hansi in India, describing it as "among the most beautiful cities, the best constructed and the most populated; it is surrounded with a strong wall, and its founder is said to be one of the great infidel kings, called Tara".[67] Upon his arrival in Sindh, Ibn Battuta mentions the Indian rhinoceros that lived on the banks of the Indus.[68]

The Sultan was erratic even by the standards of the time and for six years Ibn Battuta veered between living the high life of a trusted subordinate and falling under suspicion of treason for a variety of offences. His plan to leave on the pretext of taking another hajj was stymied by the Sultan. The opportunity for Battuta to leave Delhi finally arose around 1347 when an embassy arrived from Yuan dynastyChina asking for permission to rebuild a Himalayan Buddhist temple popular with Chinese pilgrims.[65]

Ibn Battuta was given charge of the embassy but en route to the coast at the start of the journey to China, he and his large retinue were attacked by a group of bandits.[69] Separated from his companions, he was robbed and nearly lost his life.[70] Despite this setback, within ten days he had caught up with his group and continued on to Khambhat in the Indian state of Gujarat. From there, they sailed to Calicut (now known as Kozhikode), where Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gamawould land two centuries later. While in Calicut, Battuta was the guest of the ruling Zamorin.[65] He then sailed on to Quilon (now known as Kollam), one of the busiest port cities on the Southern Coast. His journey from Calicut to Quilon lasted 10 days.[71] While Ibn Battuta visited a mosque on shore, a storm arose and one of the ships of his expedition sank.[72] The other ship then sailed without him only to be seized by a local Sumatran king a few months later.

Afraid to return to Delhi and be seen as a failure, he stayed for a time in southern India under the protection of Jamal-ud-Din, ruler of the small but powerful Nawayath sultanate on the banks of the Sharavathi river next to the Arabian Sea. This area is today known as Hosapattana and lies in the Honavar administrative district of Uttara Kannada. Following the overthrow of the sultanate, Ibn Battuta had no choice but to leave India. Although determined to continue his journey to China, he first took a detour to visit theMaldive Islands.

He spent nine months on the islands, much longer than he had intended. As a Chief Qadi, his skills were highly desirable in the formerlyBuddhist nation that had recently converted to Islam. Half-kidnapped into staying, he became chief judge and married into the royal family of Omar I. He became embroiled in local politics and left when his strict judgments in the laissez-faire island kingdom began to chafe with its rulers. In the Rihla he mentions his dismay at the local women going about with no clothing above the waist, and the locals taking no notice when he complained.[73] From the Maldives, he carried on to Sri Lanka and visited Sri Pada and Tenavaram temple.

Ibn Battuta's ship almost sank on embarking from Sri Lanka, only for the vessel that came to his rescue to suffer an attack by pirates. Stranded onshore, he worked his way back to Madurai kingdom in India. Here he spent some time in the court of the short-lived Madurai Sultanate under Ghiyas-ud-Din Muhammad Damghani,[74] from where he returned to the Maldives and boarded a Chinese junk, still intending to reach China and take up his ambassadorial post.

He reached the port of Chittagong in modern-day Bangladesh intending to travel to Sylhet to meet Shah Jalal, who became so renowned that Ibn Battuta, then in Chittagong, made a one-month journey through the mountains of Kamaru near Sylhet to meet him. [3] On his way to Sylhet, Ibn Battuta was greeted by several of Shah Jalal's disciples who had come to assist him on his journey many days before he had arrived. At the meeting in 1345 CE, Ibn Battuta noted that Shah Jalal was tall and lean, fair in complexion and lived by the mosque in a cave, where his only item of value was a goat he kept for milk, butter, and yogurt. He observed that the companions of the Shah Jalal were foreign and known for their strength and bravery. He also mentions that many people would visit the Shah to seek guidance. Ibn Battuta went further north into Assam, then turned around and continued with his original plan.

Southeast Asia[edit]

In the year 1345, Ibn Battuta travelled on to Samudra Pasai Sultanate in present day Aceh, Northern Sumatra, where he notes in his travel log that the ruler of Samudra Pasai was a pious Muslim named Sultan Al-Malik Al-Zahir Jamal-ad-Din, who performed his religious duties in utmost zeal and often waged campaigns against animists in the region. The island of Sumatra according to Ibn Battuta was rich in Camphor, Areca nut, Cloves, Tin. The madh'hab he observed was Imam Al-Shafi‘i, with similar customs as he had seen in coastal India especially among the Mappila Muslim, who were also the followers of Imam Al-Shafi‘i. At that time Samudra Pasai was the end ofDar al-Islam for no territory east of this was ruled by a Muslim ruler. Here he stayed for about two weeks in the wooden walled town as a guest of the sultan, and then the sultan provided him with supplies and sent him on his way on one of Sultan's own junks to China.[75]

Ibn Battuta then sailed to Malacca on the Malay Peninsula which he described as "Mul Jawi" he met the ruler of Malacca and stayed as a guest for three days. He then sailed to Po Klong Garai (named "Kailukari") Vietnam where he is said to have briefly met the local princess Urduja, who wrote the word Bismillah in Islamic calligraphy. Ibn Battuta described her people as opponents of the Yuan dynasty.[76] FromPo Klong Garai he finally reached Quanzhou in Fujian province, China.

China[edit]

On arriving in Quanzhou in Fujian province, China under the rule of the Mongols in the year 1345, one of the first things he noted was that Muslims referred to the city as "Zaitun" (meaning olive), but Ibn Battuta could not find any olives anywhere. He mentioned local artists and their mastery in making portraits of newly arrived foreigners these portraits Ibn Battuta noted were for security purposes. Ibn Battuta praised the craftsmen and their silk and porcelain; fruits such as plums and watermelons and the advantages of paper money.[77]He described the manufacturing process of large ships in the city of Quanzhou,[78] he also mentions Chinese cuisine and its usage of animals such as frogs, pigs and even dogs which are sold in the markets and also mentions that the chicken in China were larger in comparison.

In Quanzhou, Ibn Battuta was welcomed by the local Muslim Qadi "Fanzhang" (Judge), Sheikh al-Islam (Imam) and the leader of the local Muslim merchants all came to meet Ibn Battuta with flags, drums, trumpets and musicians.[79] Ibn Battuta noted, that the Muslim populace lived within a separate portion in the city where they had their own Mosques, Bazaars and Hospitals. In Quanzhou, he met two prominent Persians, Burhan al-Din of Kazerun and Sharif al-Din from Tabriz[80] (both of whom were influential figures noted in the Yuan History as "Sai-fu-ding" and "A-mi-li-ding").[81] While in Quanzhou he ascended the "Mount of the Hermit" and briefly visited a well-known Taoist monk in a cave.

He then traveled south along the Chinese coast to Guangzhou, where he lodged for two weeks with one of the city's wealthy merchants.[82]

From Guangzhou he went north to Quanzhou and then proceeded towards city of Fuzhou, where he took up residence with Zahir al-Din and was proud to meet Kawam al-Din and a fellow countryman named Al-Bushri of Ceuta, who had become a wealthy merchant in China. Al-Bushri accompanied Ibn Battuta northwards to Hangzhou and paid for the gifts that Ibn Battuta would present to the Mongolian Emperor Togon-temür of the Yuan Dynasty.[83]

Ibn Battuta describes Hangzhou as one of the largest cities he had ever seen,[84] and he noted its charm, describing that the city sat on a beautiful lake and was surrounded by gentle green hills.[85] Ibn Batutta mentions the city's Muslim quarter and resided as a guest with a family of Egyptian origin.[83] During his stay at Hangzhou he was particularly impressed by the large number of well-crafted and well-painted Chinese wooden ships, with colored sails and silk awnings, assembling in the canals. Later he attended a banquet of the Yuan Mongol administrator of the city named Qurtai, who according to Ibn Battuta, was very fond of the skills of local Chinese conjurers.[86] Ibn Battuta also mentions locals who worship the Solar deity.[87]

He also described floating through the Grand Canal on a boat watching crop fields, orchids, merchants in black-silk, and women in flowered-silk and priests also in silk.[88] InBeijing, Ibn Battuta referred to himself as the long-lost ambassador from the Delhi Sultanate and was invited to the Yuan imperial court of Togon-temür (who according to Ibn Battuta was worshiped by some people in China). Ibn Batutta noted that the palace of Khanbaliq was made of wood and that the ruler's "head wife" (Empress Gi) held processions in her honor.[89][90]

Ibn Battuta also reported "the rampart of Yajuj and Majuj" was "sixty days' travel" from the city of Zeitun (Quanzhou);[91] Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb notes that Ibn Battuta believed that the Great Wall of China was built by Dhul-Qarnayn to contain Gog and Magog as mentioned in the Quran.[91]

Ibn Battuta then traveled from Beijing to Hangzhou, and then proceeded to Fuzhou. Upon his return to Quanzhou, he soon boarded a Chinese junk owned by the Sultan ofSamudera Pasai Sultanate heading for Southeast Asia, whereupon Ibn Battuta was unfairly charged a hefty sum by the crew and lost much of what he had collected during his stay in China.[92]

Return home and the Black Death[edit]

After returning to Quanzhou in 1346, Ibn Battuta began his journey back to Morocco.[93] In Kozhikode, he once again considered throwing himself at the mercy of Muhammad bin Tughluq, but thought better of it and decided to carry on to Mecca. On his way to Basra he passed through the Strait of Hormuz, where he learned that Abu Sa'id, last ruler of the Ilkhanate Dynasty had died in Persia. Abu Sa'id's territories had subsequently collapsed due to a fierce civil war between the Persians and Mongols.[94]

In 1348, Ibn Battuta arrived in Damascus with the intention of retracing the route of his first hajj. He then learned that his father had died 15 years earlier[95] and death became the dominant theme for the next year or so. The Black Death had struck and he was on hand as it spread through Syria, Palestine, and Arabia. After reaching Mecca he decided to return to Morocco, nearly a quarter of a century after leaving home.[96] On the way he made one last detour to Sardinia, then in 1349 returned to Tangier by way of Fez, only to discover that his mother had also died a few months before.[97]

Al-Andalus and North Africa[edit]

After a few days in Tangier, Ibn Battuta set out for a trip to the Moor controlled territory of al-Andalus on the Iberian Peninsula. KingAlfonso XI of Castile and León had threatened to attack Gibraltar, so in 1350 Ibn Battuta joined a group of Muslims leaving Tangier with the intention of defending the port.[98] By the time he arrived, the Black Death had killed Alfonso and the threat of invasion had receded, so he turned the trip into a sight-seeing tour, traveling through Valencia and ending up in Granada.[99]

After his departure from al-Andalus he decided to travel through Morocco. On his return home, he stopped for a while in Marrakech, which was almost a ghost town following the recent plague and the transfer of the capital to Fez.[100]

Once more Ibn Battuta returned to Tangier, but only stayed for a short while. In 1324, two years before his first visit to Cairo, the West African Malian Mansa, or king of kings, Musa had passed through the same city on his own hajj and caused a sensation with a display of extravagant riches brought from his gold-rich homeland. Although Ibn Battuta never mentioned this visit specifically, when he heard the story it may have planted a seed in his mind as he then decided to cross the Sahara and visit the Muslim kingdoms on its far side.

Mali and Timbuktu[edit]

In the autumn of 1351, Ibn Battuta left Fez and made his way to the town of Sijilmasa on the northern edge of the Sahara in present-day Morocco.[101] There he bought a number of camels and stayed for four months. He set out again with a caravan in February 1352 and after 25 days arrived at the dry salt lake bed of Taghaza with its salt mines. All of the local buildings were made from slabs of salt by the slaves of the Masufa tribe, who cut the salt in thick slabs for transport by camel. Taghaza was a commercial centre and awash with Malian gold, though Ibn Battuta did not form a favourable impression of the place, recording that it was plagued by flies and the water was brackish.[102]

After a ten-day stay in Taghaza, the caravan set out for the oasis of Tasarahla (probably Bir al-Ksaib)[103][f] where it stopped for three days in preparation for the last and most difficult leg of the journey across the vast desert. From Tasarahla, a Masufa scout was sent ahead to the oasis town of Oualata, where he arranged for water to be transported a distance of four days travel where it would meet the thirsty caravan. Oualata was the southern terminus of the trans-Saharan trade route and had recently become part of the Mali Empire. Altogether, the caravan took two months to cross the 1,600 km (990 mi) of desert from Sijilmasa.[104]

From there, Ibn Battuta travelled southwest along a river he believed to be the Nile (it was actually the river Niger), until he reached the capital of the Mali Empire.[g] There he met MansaSuleyman, king since 1341. Ibn Battuta disapproved of the fact that female slaves, servants and even the daughters of the sultan went about exposing parts of their bodies not befitting a Muslim.[106] He left the capital in February accompanied by a local Malian merchant and journeyed overland by camel to Timbuktu.[107]Though in the next two centuries it would become the most important city in the region, at that time it was a small city and relatively unimportant.[108] It was during this journey that Ibn Battuta first encountered a hippopotamus. The animals were feared by the local boatmen and hunted with lances to which strong cords were attached.[109] After a short stay in Timbuktu, Ibn Battuta journeyed down the Niger to Gao in a canoe carved from a single tree. At the time Gao was an important commercial center.[110]

After spending a month in Gao, Ibn Battuta set off with a large caravan for the oasis of Takedda. On his journey across the desert, he received a message from the Sultan of Morocco commanding him to return home. He set off for Sijilmasa in September 1353, accompanying a large caravan transporting 600 female slaves, and arrived back in Morocco early in 1354.[111]

Ibn Battuta's itinerary gives scholars a glimpse as to when Islam first began to spread into the heart of west Africa.[112]

Rihla[edit]

See also: Rihla

After returning home from his travels in 1354, and at the instigation of the Marinid ruler of Morocco, Abu Inan Faris, Ibn Battuta dictated an account of his journeys to Ibn Juzayy, a scholar whom he had previously met in Granada. The account is the only source for Ibn Battuta's adventures. The full title of the manuscript تحفة النظار في غرائب الأمصار وعجائب الأسفار may be translated as A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling. However, it is often simply referred to as the Rihla الرحلة, or "The Journey".[113]

There is no indication that Ibn Battuta made any notes during his twenty-nine years of travelling. When he came to dictate an account of his experiences he had to rely on memory and manuscripts produced by earlier travellers. Ibn Juzayy did not acknowledge his sources and presented some of the earlier descriptions as Ibn Battuta's own observations. When describing Damascus, Mecca, Medina and some other places in the Middle East, he clearly copied passages from the account by the Andalusian Ibn Jubayr which had been written more than 150 years earlier.[114] Similarly, most of Ibn Juzayy's descriptions of places in Palestine were copied from an account by the 13th-century traveller Muhammad al-Abdari.[115]

Scholars do not believe that Ibn Battuta visited all the places he described and argue that in order to provide a comprehensive description of places in the Muslim world, he relied on hearsay evidence and made use of accounts by earlier travellers. For example, it is considered very unlikely that Ibn Battuta made a trip up the Volga River from New Sarai to visit Bolghar[116] and there are serious doubts about a number of other journeys such as his trip to Sana'a in Yemen,[117] his journey from Balkh to Bistam in Khorasan[118] and his trip around Anatolia.[119] Some scholars have also questioned whether he really visited China.[120] However, even if the Rihla is not fully based on what its author personally witnessed, it provides an important account of much of the 14th-century world.

Ibn Battuta often experienced culture shock in regions he visited where the local customs of recently converted peoples did not fit in with his orthodox Muslim background. Among the Turks and Mongols, he was astonished at the freedom and respect enjoyed by women and remarked that on seeing a Turkish couple in a bazaar one might assume that the man was the woman's servant when he was in fact her husband.[121] He also felt that dress customs in the Maldives, and some sub-Saharan regions in Africa were too revealing.

Little is known about Ibn Battuta's life after completion of his Rihla in 1355. He was appointed a judge in Morocco and died in 1368 or 1369.[122]

Manuscripts and publication[edit]

Ibn Battuta's work was unknown outside the Muslim world until the beginning of the 19th century when the German traveller-explorerUlrich Jasper Seetzen (1767–1811) acquired a collection of manuscripts in the Middle East, among which was a 94-page volume containing an abridged version of Ibn Juzayy's text. Three extracts were published in 1818 by the German orientalist Johann Kosegarten.[123] A fourth extract was published the following year.[124] French scholars were alerted to the initial publication by a lengthy review published in the Journal de Savants by the orientalist Silvestre de Sacy.[125]

Three copies of another abridged manuscript were acquired by the Swiss traveller Johann Burckhardt and bequeathed to the University of Cambridge. He gave a brief overview of their content in a book published posthumously in 1819.[126] The Arabic text was translated into English by the orientalist Samuel Lee and published in London in 1829.[127]

In the 1830s, during the French occupation of Algeria, the Bibliothèque Nationale (BNF) in Paris acquired five manuscripts of Ibn Battuta's travels, in which two were complete.[h]One manuscript containing just the second part of the work is dated 1356 and is believed to be Ibn Juzayy's autograph.[132] The BNF manuscripts were used in 1843 by the Irish-French orientalist Baron de Slane to produce a translation into French of Ibn Battuta's visit to the Sudan.[133] They were also studied by the French scholars Charles Defrémery and Beniamino Sanguinetti. Beginning in 1853 they published a series of four volumes containing a critical edition of the Arabic text together with a translation into French.[134] In their introduction Defrémery and Sanguinetti praised Lee's annotations but were critical of his translation which they claimed lacked precision, even in straightforward passages.[i]

In 1929, exactly a century after the publication of Lee's translation, the historian and orientalist Hamilton Gibb published an English translation of selected portions of Defrémery and Sanguinetti's Arabic text.[136] Gibb had proposed to the Hakluyt Society in 1922 that he should prepare an annotated translation of the entire Rihla into English.[137] His intention was to divide the translated text into four volumes, each volume corresponding to one of the volumes published by Defrémery and Sanguinetti. The first volume was not published until 1958.[138] Gibb died in 1971, having completed the first three volumes. The fourth volume was prepared by Charles Beckingham and published in 1994.[139]Defrémery and Sanguinetti's printed text has now been translated into number of other languages.

Legacy[edit]

Ibn Battuta himself stated according to Ibn Juzayy that:

"To the world of today the men of medieval Christendom

already seem

remote and unfamiliar. Their names and deeds are recorded in

our history-books, their monuments still adorn our cities, but our kinship with

them is a thing unreal, which costs an effort of

imagination. How much more must this apply to the great Islamic civilization,

that stood over against medieval Europe, menacing its existence and yet linked

to it by a hundred ties that even war and fear could not sever. Its monuments

too abide, for those who may have the fortunate to visit

them, but its men and manners are to most of us utterly unknown, or dimly

conceived in the romantic image of the Arabian Nights. Even for the specialist

it is difficult to reconstruct their lives and see them as they were.

Histories and biographies there are in quantity, but the

historians for all their picturesque details, seldom show the ability to select

the essential and to give their figures

that touch of the intimate which makes them live again for the reader. It is in

this faculty that Ibn Battuta excels."

Thus begins the book, "Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and

Africa 1325-1354" published by Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta, also known as Shams ad -

Din, was born at Tangier, Morocco, on the 24th February 1304 C.E.

(703 Hijra). He left Tangier on Thursday, 14th June, 1325 C.E. (2nd

Rajab 725 A.H.), when he was twenty one

years of age. His travels lasted for about thirty years,

after which he returned to Fez, Morocco at the court of Sultan Abu 'Inan and dictated

accounts of his journeys to Ibn Juzay. These are known as the famous Travels

(Rihala) of Ibn Battuta. He died at Fez in 1369 C.E.

Ibn Battuta was the only medieval traveller who is known to have

visited the lands of every Muslim ruler of his time. He also travelled in

Ceylon (present Sri Lanka), China and Byzantium and South Russia. The mere

extent of his travels is estimated at no less than 75,000 miles, a figure which

is not likely to have been surpassed before the age of steam.

Travels

In the course of his first journey, Ibn Battuta travelled

through Algiers, Tunis, Egypt, Palestine and Syria to Makkah. After visiting

Iraq, Shiraz and Mesopotamia he once more returned to perform the Hajj at

Makkah and remained there for three years. Then travelling to Jeddah he went to

Yemen by sea, visited Aden andset sail for Mombasa, East Africa. After going up

to Kulwa he came back to Oman and repeated pilgrimage to Makkah in 1332 C.E.

via Hormuz, Siraf, Bahrain and Yamama. Subsequently he set out with the purpose

of going to India, but on reaching Jeddah, he appears to have changed his mind

(due perhaps to the unavailability of a ship bound for India), and revisited

Cairo,

Palestine and Syria, thereafter arriving at Aleya (Asia

Minor) by sea and travelled across Anatolia and Sinope. He then crossed the

Black Sea and after long wanderings he reached Constantinople through Southern

Ukraine.

On his return, he visited Khurasan through Khawarism (Khiva)

and having visited all the important cities such as Bukhara, Balkh, Herat, Tus,

Mashhad and Nishapur, he crossed the Hindukush mountains via the 13,000 ft

Khawak Pass into Afghanistan and passing through Ghani and Kabul entered India.

After visiting Lahri (near modern Karachi), Sukkur, Multan, Sirsa and Hansi, he

reached Delhi. For several years Ibn Battuta enjoyed the patronage of Sultan

Mohammad Tughlaq, and was later sent as Sultan's envoy to China. Passing

through Cental India and Malwa he took ship from Kambay for Goa, and after

visiting many thriving ports along the Malabar coast he reached the Maldive

Islands, from which he crossed to Ceylon.

Continuing his journey, he landed on the Ma'bar (Coromandal)

coast and once more returning to the Maldives he finally set sail for Bengal

and visited Kamrup, Sylhet and Sonargaon (near Dhaka). Sailing along the Arakan

coast he came to Sumatra and later landed at Canton via Malaya and Cambodia. In

China he travelled northward to Peking through Hangchow. Retracing his steps he

returned to Calicut and taking ship came to Dhafari and Muscat, and passing

through Paris (Iran), Iraq, Syria, Palestine and Egypt made his seventh and

last pilgrimage to Makkah in November 1348 C.E. and then returned to his home

town of Fez.

His travels did not end here - he later visited Muslim Spain

and the lands of the Niger across the Sahara.

On his return to Fez, Ibn Battuta dictated the accounts

ofhis travels to Ibn Juzay al-Kalbi (1321-1356 C.E.) at the court of Sultan Abu

Inan (1348-1358 C.E). Ibn Juzay took three months to accomplish this work

,which he finished on 9th December 1355 C.E.

Writings

In order to experience the flavour of Ibn Battuta's

narrative one must sample a few extracts. The following passage illustrates the

system of social security in operation in the Muslim world in the early 14th

century C.E. :

"The variety and expenditure of the religious

endowmentsat

Damascus are beyond computation. There are endowments in aid

of persons who cannot undertake the pilgrimage to Makkah, out of which ate paid

the expenses of those who go in their stead. There are other endowments for

supplying wedding outfits to girls whose families are unable to provide them,

and others for the freeing of prisoners. There are endowments for travellers,

out of the revenues of which they are given food, clothing, and the expenses of

conveyance to their countries. Then there are endowments for the improvement and

paving of the streets, because all the lanes in Damascus have pavements on either

side, on which the foot passengers walk, while those who ride use the roadway

in the centre". p.69, ref l

Here is another example which describes Baghdad in the early

14th century C.E. :

"Then we travelled to Baghdad, the Abode of Peace

andCapital of

Islam. Here there are two bridges like that at Hilla, on

which the people promenade night and day, both men and women. The baths at Baghdad

are numerous and excellently constructed, most of them being painted with

pitch, which has the appearance of black marble.

This pitch is brought from a spring between Kufa and Basra,

from which it flows continually. It gathers at the sides of the spring like clay

and is shovelled up and brought to Baghdad. Each establishment has a number of

private bathrooms, every one of which has also

a wash-basin in the corner, with two taps supplying hot and

cold water. Every bather is given three towels, one to wear round his waist

when he goes in, another to wear round his waist when he comes out, and the

third to dry himself with." p.99, ref 1

In the next example Ibn Battuta describes in great

detailsome of the crops and fruits encountered on his travels:

"From Kulwa we sailed to Dhafari [Dhofar], at the

extremity of Yemen. Thoroughbred horses are exported from here to India, the passage

taking a month with favouring wind.... The inhabitants cultivate millet and

irrigate it from very deep wells, the water from which is raised in a large

bucket drawn by a number of ropes. In the neighbourhood of the town there are

orchards with many banana trees. The bananas are of immense size; one which was

weighed in my presence scaled twelve ounces and was pleasant to the taste and

very sweet. They also grow betel-trees and coco-palms, which

are found only in India and the town of Dhafari." p.113, ref 1

Another example of In Battuta's keen observation is seen in the

next passage:

"Betel-trees are grown like vines on can trellises or

else trained up coco-palms. They have no fruit and are only grown for their

leaves.

The Indians have a high opinion of betel, and if a man

visits a friend and the latter gives him five leaves of it, you would think he

had given him the world, especially if he is a prince or notable. A gift of betel

is a far greater honour than a gift of gold and silver. It is used in the

following way: First one takes areca-nuts, which are like nutmegs, crushes them

into small bits and chews them. Then the betel leaves are taken, a little chalk

is put on them, and they are chewed with the areca-nuts." p.114, ref 1

Ibn Battuta - The Forgotten Traveller Ibn Battuta's sea

voyages and references to shipping reveal that the Muslims completely dominated

the maritime activity of the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean, and

the Chinese waters. Also it is seen that though the Christian traders were

subject to certain restrictions, most of the economic

negotiations were transacted on the basis of equality and mutual respect. Ibn

Battuta, one of the most remarkable travellers of all time, visited China sixty

years after Marco Polo and in fact travelled 75,000 miles, much more than Marco

Polo. Yet Battuta is never

mentioned in geography books used in Muslim countries, let alone

those in the West. Ibn Battuta's contribution to geography is unquestionably as

great as that of any geographer yet the accounts of his travels are not easily

accessible except to the specialist. The omission of reference to Ibn Battuta's

contribution in

geography books is not an isolated example. All great

Muslims whether historians, doctors, astronomers, scientists or chemists suffer

the same fate. One can understand why these great

Muslims are ignored by the West. But the indifference of the

Muslim governments is incomprehensible. In order to combat the inferiority

complex that plagues the Muslim Ummah, we must rediscover the contributions of

Muslims in fields such as science, medicine, engineering, architecture and

astronomy. This will encourage contemporary young Muslims to strive in these

fields and not think that major success is beyond their reach.

Ibn Battuta was perhaps the greatest traveler of the Middle

Ages, having traveled about 75,000 miles in 29 years! He is especially

important to history because of his written accounts (reports) of his travels.

From these records we can learn about the cultures that he visited. The book

about his travels is the only historical source of information about many of

the places he visited which included the East African coast, the Empire of Mali

in West Africa, Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Turkey, India, China, Spain, and many, many

more! As a Muslim, he took advantage of the generosity shown to pilgrims and

travelers in the Empire. He was often given gifts (of horses, gold, and even

slaves) and stayed for free in dormitories, private homes, and even in the

palaces of Muslim rulers. For seven years he worked for the Sultan in Delhi,

India. On his travels he met several Sultans who welcomed him into their

company. His descriptions are filled with adventures - he almost died several

times. He survived robbers, shipwrecks, pirates, wars, and the Black Death (or

Bubonic Plague).

pengembara Berber Maroko. Atas dorongan Sultan Maroko, Ibnu

Batutah mendiktekan beberapa perjalanan pentingnya kepada seorang sarjana

bernama Ibnu Juzay, yang ditemuinya ketika sedang berada di Iberia. Meskipun

mengandung beberapa kisah fiksi, Rihlah merupakan catatan perjalanan dunia

terlengkap yang berasal dari abad ke-14.

Hampir semua yang diketahui tentang kehidupan Ibnu Batutah

datang dari dirinya sendiri.

Meskipun dia mengiklankan bahawa hal-hal yang diceritakannya

adalah apa yang dia lihat atau dia alami, kita tak bisa tahu kebenaran dari

cerita tersebut. Lahir di Tangier, Maroko antara tahun 1304 dan 1307, pada usia

sekitar dua puluh tahun Ibnu Batutah berangkat haji -- ziarah ke Mekah. Setelah

selesai, dia melanjutkan perjalanannya hingga melintasi 120.000 kilometer

sepanjang dunia Muslim (sekitar 44 negara modern).

Perjalanannya ke Mekah melalui jalur darat, menyusuri pantai

Afrika Utara hingga tiba di Kairo. Pada titik ini ia masih berada dalam wilayah

Mamluk, yang relatif aman. Jalur yang umu digunakan menuju Mekah ada tiga, dan

Ibnu Batutah memilih jalur yang paling jarang ditempuh: pengembaraan menuju

sungai Nil, dilanjutkan ke arah timur melalui jalur darat menuju dermaga Laut

Merah di 'Aydhad. Tetapi, ketika mendekati kota tersebut, ia dipaksa untuk

kembali dengan alasan pertikaian lokal.

Kembail ke Kairo, ia menggunakan jalur kedua, ke Damaskus

(yang selanjutnya dikuasai Mamluk), dengan alasan keterangan/anjuran seseorang

yang ditemuinya di perjalanan pertama, bahwa ia hanya akan sampai di Mekah jika

telah melalui Suriah. Keuntungan lain ketika memakai jalur pinggiran adalah

ditemuinya tempat-tempat suci sepanjang jalur tersebut -- Hebron, Yerusalem,

dan Betlehem, misalnya -- dan bahwa penguasa Mamluk memberikan perhatian khusus

untuk mengamankan para peziarah.

Setelah menjalani Ramadhan di Damaskus, Ibnu Batutah

bergabung dengan suatu rombongan yang menempuh jarak 800 mil dari Damaskus ke

Madinah, tempat dimakamkannya Muhammad. Empat hari kemudian, dia melanjutkan

perjalanannya ke Mekah. Setelah melaksanakan rangkaian ritual haji, sebagai

hasil renungannya, dia kemudian memutuskan untuk melanjutkan mengembara. Tujuan

selanjutnya adalah Il-Khanate (sekarang Iraq dan Iran.

Dengan cara bergabung dengan suatu rombongan, dia melintasi

perbatasan menuju Mesopotamia dan mengunjungi najaf, tempat dimakamkannya

khalifah keempat Ali. Dari sana, dia melanjutkan ke Basrah, lalu Isfahan, yang

hanya beberapa dekade jaraknya dengan penghancuran oleh Timur. Kemudian Shiraz

dan Baghdad (Baghdad belum lama diserang habis-habisan oleh Hulagu Khan).

Di sana ia bertemu Abu Sa'id, pemimpin terakhir Il-Khanate.

Ibnu Batutah untuk sementara mengembara bersama rombongan penguasa, kemudian

berbelok ke utara menuju Tabriz di Jalur Sutra. Kota ini merupakan gerbang

menuju Mongol, yang merupakan pusat perdagangan penting.

Setelah perjalanan ini, Ibnu Batutah kembali ke Mekah untuk

haji kedua, dan tinggal selama setahun sebelum kemudian menjalani pengembaraan

kedua melalui Laut Merah dan pantai Afrika Timur. Persinggahan pertamanya

adalah Aden, dengan tujuan untuk berniaga menuju Semenanjung Arab dari sekitar

Samudera Indonesia. Akan tetapi, sebelum itu, ia memutuskan untuk melakukan

petualangan terakhir dan mempersiapkan suatu perjalanan sepanjang pantai

Afrika.

Menghabiskan sekitar seminggu di setiap daerah tujuannya,

Ibnu Batutah berkunjung ke Ethiopia, Mogadishu, Mombasa, Zanzibar, Kilwa, dan

beberapa daerah lainnya. Mengikuti perubahan arah angin, dia bersama kapal yang

ditumpanginya kembali ke Arab selatan. Setelah menyelesaikan petualangannya,

sebelum menetap, ia berkunjung ke Oman dan Selat Hormuz. Setelah selesai, ia

berziarah ke Mekah lagi.

Setelah setahun di sana, ia memutuskan untuk mencari

pekerjaan di kesultanan Delhi. Untuk keperluan bahasa, dia mencari penterjemah

di Anatolia. Kemudian di bawah kendali Turki Saljuk, ia bergabung dengan sebuah

rombongan menuju India. Pelayaran laut dari Damaskus mendaratkannya di Alanya

di pantai selatan Turki sekarang. Dari sini ia berkelana ke Konya dan Sinope di

pantai Laut Hitam.

Setelah menyeberangi Laut Hitam, ia tiba di Kaffa, di

Crimea, dan memasuki tanah Golden Horde. Dari sana ia membeli kereta dan

bergabung dengan rombongan Ozbeg, Khan dari Golden Horde, dalam suatu

perjalanan menuju Astrakhan di Sungai Volga.

Can you name some of the countries in which he traveled?

Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta, was born in Tangier, Morocco, on the 24th of February 1304 C.E. (703 Hijra) during the time of the Marinid dynasty. He was commonly known as Shams ad-Din. His family was of Berber origin and had a tradition of service as judges. After receiving an education in Islamic law, he chose to travel. He left is house in June 1325, when he was twenty one years of age and set off from his hometown on a hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca, a journey that took him 16 months. He did not come back to Morocco for at least 24 years after that. His journey was mostly by land. To reduce the risk of being attacked, he usually chose to join a caravan. In the town of Sfax, he got married. He survived wars, shipwrecks, and rebellions.

He first began his voyage by exploring the lands of the Middle East. Thereafter he sailed down the Red Sea to Mecca. He crossed the huge Arabian Desert and traveled to Iraq and Iran. In 1330, he set of again, down the Red Sea to Aden and then to Tanzania. Then in 1332, Ibn Battuta decided to go to India. He was greeted open heartedly by the Sultan of Delhi. There he was given the job of a judge. He stayed in India for a period of 8 years and then left for China. Ibn Battuta left for another adventure in 1352. He then went south, crossed the Sahara desert, and visited the African kingdom of Mali.

Finally, he returned home at Tangier in 1355. Those who were lodging Ibn Battuta’s grave Western Orient lists could not believe that Ibn Battuta visited all the places that he described. They argued that in order to provide a comprehensive description of places in the Muslim world in such a short time, Ibn Battuta had to rely on hearsay evidence and make use of accounts by earlier travelers.

Ibn Battuta often experienced culture shock in regions he visited. The local customs of recently converted people did not fit his orthodox Muslim background. Among Turks and Mongols, he was astonished at the way women behaved. They were given freedom of speech. He also felt that the dress customs in the Maldives and some sub-Saharan regions in Africa were too revealing.

Death:

After the completion of the Rihla in 1355, little is known about Ibn Battuta’s life. He was appointed a judge in Morocco and died in 1368. Nevertheless, the Rihla provides an important account of many areas of the world in the 14th century.

http://www.sfusd.k12.ca.us/schwww/sc...tlasAfrica.jpg

For an extensive website on Ibn Battuta, see Ibn Battuta

- A Virtual Tour of the 14th Century.

See a short biography with some passages from his book at

"Ibn Battuta - The Great Traveller" (by A.S. Chughtai).

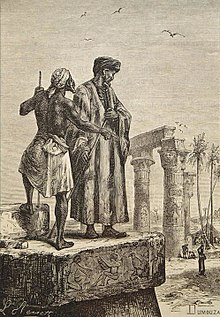

For an image of a Saharan traveler meeting a rich king in

West Africa, the same as to the right (reminiscent of Ibn Battuta). The Catalan

Map was completed in 1375 AD.

See National Geographic, 12/91 for more information.

http://www.sfusd.k12.ca.us/schwww/sc...BattutaMap.gif

From the Catalan Atlas, National Library of France,

Paris. It was completed in 1375.

Rough Map of Ibn Battuta's Travels - about 75,000 miles

in 29 years!

Ibn Battuta started his trip in Tangier, Morocco, going

east on his first hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca.

References

1. Ibn Buttuta,

Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1345, Published by Routledge and Kegan Paul (ISBN O 7100 9568 6)

2. The Introduction

to the "Voyages of Ibn Battutah" by Vincent Monteil in The Islamic

Review and Arab Affairs. March 1970: 30-37

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar